How can we apply the wisdom of the ancients to the modern workplace? Philosopher Brennan Jacoby considers the four classical virtues that make for great collaboration – and the vices that stand in the way.

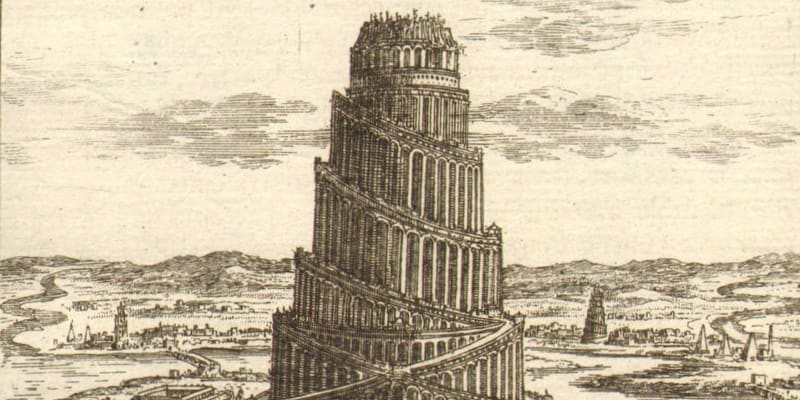

There was once an ancient people who set out to build the greatest tower the world had ever seen. Through pooling their collective knowledge and skill, progress was rapid – at least at the start. But then their work was disrupted by a god who gifted each team a different language. The project became increasingly frustrating, then impossible. It was quietly set to one side.

Our current working landscape is not unlike a contemporary version of Babel, in which new technological advancements, social media and communication tools are regularly thrown into the mix. We often find ourselves working on projects spread over many years, multiple continents and involving tens or even hundreds of team members. In fact, the challenges collaborators face today make the Tower of Babel look like a project that might have been finished off over lunch by the graduate trainee team from the sales department.

The need for collaboration

While there’s something truly moving about harnessing collective activities to form the world we all rely on, it’s vital to identify and nurture what one might term ‘the collaborative virtues’ – a set of psychological attributes on which good teamwork depends. Below are four negative character traits that can lead our combined efforts astray – and the steps that can be taken by individuals, teams and organisations to cultivate the virtues of collaboration.

Our current working landscape is not unlike a contemporary version of Babel

From loafing to clarity

All teams wishing to succeed must address a natural inclination toward laziness. Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and theatre, was the ultimate loafer – preferring drinking and dancing to anything resembling work. In the context of collaborative work, this vice includes the daily temptations to underprepare for meetings, to fail to listen properly to colleagues, or to share a draft of work when it’s still half-baked – hoping that our teammate or manager will take on the heavy lifting required to finish it off properly.

While some loafing results from a deficiency in motivation, the deeper reason is often because we’re unsure what we’re meant to be doing, or because we’re so busy that we haven’t had time to work out what we really think about a project. This lack of clarity inhibits us from voicing suggestions or working in an area we fear may be someone else’s territory.

Tips for gaining clarity

In collaborative terms, be more like the goddess of wisdom, Athena – the cool head who always finds rational solutions while others are mired in emotional conflicts, jealousy and resentment. For individuals, this means clarifying your specific role, and the roles of others. While these roles naturally change over time, by building in a series of preagreed moments over the course of a project, you can review and, if necessary, redefine your responsibilities.

Businesses should clarify their broader organisational purpose. Roman emperors realised that even wielding the power of life and death was rarely sufficient motivation. In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius noted: “At dawn, when you have trouble getting out of bed, tell yourself: ‘I have to go to work – as a human being… Is this what I was created for? To huddle under the blankets and stay warm?’” Remember that your defining characteristic is to work with others.

From placation to contention

It’s natural to assume that a fruitful collaborative office is one where everyone gets on well, meetings are full of agreement and shared insights and there’s no conflict. We tend to associate collaboration with harmony. Yet in most cases, contention is a hugely productive force. By having to defend our deepest, most important insights against intelligent criticism, we find more powerful ways to express our ideas, recognise weaknesses in our plans and learn to hedge against these deficiencies.

Follow the lead of ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, who went around questioning his fellow Athenians on a range of topics, trying to help them understand where they might have started from the wrong assumptions or leapt to the wrong conclusion. His goal was to help them bring out the wisdom they already had in themselves.

Don’t replicate the mistake of the Athenian government, which decided that Socrates was a corruptor of youth and sentenced him to death by drinking hemlock. As individuals, teams, and organisations, we should revise our understanding of contention and actively seek it out in more productive ways.

Marcus Aurelius extolled the virtues of finding meaning in your work

Tips for embracing contention

Practise the art of the indirect question. This can be much more conducive to successful collaboration and can open up contentious topics without ruffling too many feathers. Instead of asking, “Did you make your sales goal?” ask, “How have sales been going?” Business leaders need to role-model directness. Ares, Greek god of war and action, was revered for his decisiveness faced with awkward or uncomfortable situations. Myth says that he inspired the Spartans to stand up to the intimidating Persian army at Thermopylae and, by doing so, save Greece from being enslaved. Leaders must encourage opposition and disagreement, but practise being able to give and receive it good-naturedly.

From posturing to realism

While many businesses aspire to develop cultures where authenticity, honesty and vulnerability are highly valued, the reality is often quite different. Impostor syndrome runs rife through many organisations, and ironically, the more prestigious the firm, the more likely employees are to feel that they have been hired by accident.

We make up for this by posturing. We studiously scribble in our notebook rather than openly voicing what could be a laughably naive suggestion. We nod as if in deep agreement, without understanding what we’re agreeing to. Or we resort to ‘appearing professional’, using specialist jargon or acronyms that we don’t quite understand.

The greatest posturer among classical heroes is undoubtedly Heracles, who insists on single-handedly performing a series of impossible tasks. A saner, simpler and swifter approach might have been to team up with friends and pool resources from the start.

In contrast, the arch-realist and master collaborator is Odysseus. His main weapons are tact, persuasion and wisdom. He helps his crew outwit physically stronger opponents such as the Cyclops through wordplay alone. The key is realising that we are not alone, that most minds work in basically the same way and that most colleagues are quite often as intimidated, anxious and uncertain as we are.

Tips for humility

Become more comfortable with ambivalence. This doesn’t mean having mixed feelings, but being able to hold competing ideas in your mind and to weigh them up slowly without feeling the need to instantly choose a position.

Organisations may want to consider investing in better corporate art and design. One of the tasks that works of art should ideally accomplish is to take us more reliably into the minds of people we are intimidated by in order to show us the more average, muddled and fretful experiences that they have. In that way, we’ll not feel so barred from taking part ourselves. Art can remind us that it’s OK to feel worried, insecure and anxious – and yet give us the courage to join in anyway.

Managers should be more like Zeus – a highly skilled facilitator

From misplaced confidence to appreciation

We might imagine that overconfidence is only a problem for a small group of narcissists, but in reality many of us have an in-built overconfidence in certain areas of our working life that can cripple collaboration.

It can be frightening to admit that an outcome that is crucial to one’s own ambitions lies in the hands of colleagues. But a successful collaborator is someone who is able to live with the anxiety of dependence and who also deeply appreciates those they depend on. When we work alongside others, our collective strengths and wisdom go way beyond anything that one fragile individual might accomplish.

Tips for appreciation

Replace email with a genuine conversation, where you make your intentions clear and come away with a final outcome. This greatly reduces misunderstanding and aids longer-term efficiency and creativity.

Managers should be more like Zeus. Not just a thunderbolt hurler, Zeus is the masterly board chairman – a highly skilled facilitator who holds the boundaries, allows the other gods to speak up, articulate grievances and find solutions that are acceptable to all. Take your cue from the world of sports, where football pundits and players routinely give credit to ‘assists’ from teammates. Building strong, collaborative organisations is not about investing in better bricks, but finding ways to strengthen the mortar between all the bricks.

Final thoughts

Civilisation is, at heart, a deeply collaborative project. The Greek word for a private individual, someone who resolutely pursues only personal rather than public interests, is idiotes – the root of the word ‘idiot’ in many languages. Successful collaboration may be supported by technological advances, but to collaborate optimally, we also need to place our trust in some very old ways of doing things – using face-to-face conversation rather than email, and carving out space in the working day to take stock, think and gain clarity in solitude.